The RESTRICT Act Is Not About TikTok

PLUS: When Good Laws Meet Bad Governments

Your weekly dose of Seriously Risky Business news is written by Tom Uren, edited by Patrick Gray with help from Catalin Cimpanu. It's supported by the Cyber Initiative at the Hewlett Foundation and founding corporate sponsor Proofpoint.

Last week a bipartisan group of US senators unveiled the RESTRICT Act, legislation designed to give the executive branch new powers to deal with the threats posed by technology from six "foreign adversaries" — China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Cuba and Venezuela. This legislation has broad bi-partisan support, with a dozen senators across both the Democratic and Republican parties supporting it.

In a press conference announcing the legislation one of the bill's chief sponsors, Senator Mark Warner, cited Kaspersky anti-virus, Huawei and now TikTok as evidence of the ongoing problems posed by foreign technologies. Warner described current tools to deal with these kinds of threats as "limited", adding that the US "lack[s], at this moment in time, a holistic, interagency, whole-of-government approach".

The RESTRICT Act is intended to fix that by directing the Department of Commerce to establish processes to identify and mitigate risks posed by foreign interests in information and communications technology products. The Act doesn't require any particular response to a threat, but instead gives the Secretary of Commerce new powers to deal with them. Warner described these as a "series of mitigation tools… up to and including the opportunity to ban [a firm]".

And when it comes to competing with China in particular, empowering the executive branch with these kinds of authorities just seems like fair play. Many US-based technology and social media companies are banned within mainland China, so why should a company like TikTok get free reign when it comes to operating in the US?

Half a dozen "foreign adversaries" are specified in the RESTRICT Act, but China is obviously the big one here. It has strategic plans to boost indigenous innovation and technological self-sufficiency and has a National Intelligence Law that can compel organisations to assist in national intelligence efforts. The US Intelligence Community's Annual Threat Assessment, which was released last week, assesses:

If Beijing feared that a major conflict with the United States were imminent, it almost certainly would consider undertaking aggressive cyber operations against U.S. homeland critical infrastructure and military assets worldwide. Such a strike would be designed to deter U.S. military action by impeding U.S. decisionmaking, inducing societal panic, and interfering with the deployment of U.S. forces.

[Risky Business News has an excellent short summary of the threat assessment from our colleague Catalin Cimpanu.]

So it is no surprise the White House issued a statement supporting the RESTRICT legislation and pointed out that it provided a systematic framework for addressing technology-based threats:

This legislation would provide the U.S. government with new mechanisms to mitigate the national security risks posed by high-risk technology businesses operating in the United States. Critically, it would strengthen our ability to address discrete risks posed by individual transactions, and systemic risks posed by certain classes of transactions involving countries of concern in sensitive technology sectors.

We also like the Act, particularly its requirement that the Director of National Intelligence educate the business community and public by publishing a rationale whenever a transaction is denied or mitigated. In other words, actions require justifications.

Jon Bateman, a Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment, told Seriously Risky Business he has some concerns that these new powers could be used too aggressively.

We think the reflexively anti-PRC political environment that may be motivating lawmakers to advance legislation may also make it likely the powers the Act grants will be overused. Bateman agrees.

He did point out, however, that the administration has a good track record so far and a similar executive authority, the ICTS Supply Chain Rule, had not been overused. And after all, the whole point of the legislation is to replace politics with process by introducing a framework for working through difficult supply chain and technology problems.

That's all well and good, but we do wonder what will happen with authorities like this if Donald Trump is re-elected to a second term.

When Good Laws Meet Bad Governments

Rest of World has taken a look at Cambodia's draft cyber security law and experts' concerns it could be abused to reinforce Prime Minister Hun Sen's grip on power. Per the article:

…the law would allow the government to seize operating systems and copy and filter data from entities unable to mitigate the impacts of a "cybersecurity threat or cybersecurity incident at the critical level" — defined broadly as an event that could cause "significant harm" to "national security, national defense, foreign relations, the economy, public health, safety or public order."

Funnily enough, some of these elements are also present in Australia's Security of Critical Infrastructure Act (SOCI). So why is this type of law bad in Cambodia but okay down under?

Under Australia's laws, if a cyber security incident is bad enough, the Home Affairs Minister can compel a critical infrastructure organisation "to do, or refrain from doing, a specified act or thing" and it must accept government assistance. This assistance can even take the form of "intervention requests" where ASD, Australia's signals intelligence agency, can take over to some degree. Per the Australian government's explainer:

An intervention request may include but is not limited to a direction to access or modify a computer that is part of the asset, remove or disconnect a computer from a network that is part of the asset, or access, copy, alter or delete a computer program that is installed on a computer that is, or is part of, the asset to which the Ministerial authorisation relates.

It does feel just a bit Orwellian, particularly as this is the kind of government assistance that you can't refuse. The legislation was controversial as a result, and both AWS and Google argued these "step-in" powers weren't suitable for complex critical infrastructure. Their take was that the government wouldn't be able to understand complex cloud environments and that bumbling around could well make things worse.

The government intervention powers, however, came about as a direct response to a problem the government had identified. ASD Director Rachel Noble told a parliamentary committee hearing into the then draft legislation that there had been a significant ransomware incident where the affected firm appeared to deliberately keep the government in the dark. Noble said the ASD learnt of the incident via media reports and that engagement was "sluggish".

"This incident had a national impact on our country. On day 14, we're able to only provide them with generic protection advice, and their network is still down. Three months later, they get reinfected, and we start again", Noble told the hearing.

So given Australia's experience, the intent of Cambodia's draft legislation could make sense. But what works in Australia could be a bridge too far in Cambodia. The Australian legislation has some checks and balances and there are genuinely independent oversight agencies.

The real problem here is Cambodia's governance.

Gatri Priyandita, from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute's cyber centre, told Rest of World "the intention of the regime matters, and Cambodia’s approach to security is very much driven by protection of the regime". Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen has held power in some capacity since 1985 and Freedom House assesses that Cambodia is "not free".

Three Reasons to be Cheerful this Week:

- NetWire RAT website administrator detained: Croatian authorities arrested an individual accused of operating the website selling Netwire RAT malware. The US government also seized the website domain. FBI efforts on analysing the malware are discussed further below in "When Popups Are a Good Thing".

- Biden Administration places security focus on the cloud: Politico has two good reports on the US government pushing to improve security at cloud providers. That's great news as cloud providers' promises of better security haven't exactly matched reality. The market concentration also introduces a source of systemic vulnerability too: Marc Rogers, chief security officer at Q-Net Security told Politico "a single cloud provider going down could take down the internet like a stack of dominos".

- CISA scans critical infrastructure for ransomware vulnerabilities: The US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency officially launched its Ransomware Vulnerability Warning Pilot program to proactively warn critical infrastructure organisations when they have vulnerabilities that are commonly exploited by ransomware actors. There are a bunch of similar efforts in the UK and other European countries.

Sponsor Section

Seriously Risky Business is supported by the Hewlett Foundation's Cyber Initiative and corporate sponsor Proofpoint.

Proofpoint's 2023 State of the Phish report finds that paying ransoms is a coin toss.

Heads or tails? About 52% of survey respondents infected with #ransomware regained access to their #data after making a single payment. That’s slightly better odds than a coin flip.

— Proofpoint (@proofpoint) 3:05 PM ∙ Mar 14, 2023

Our new report details the ins and outs of ransomware, and other threats. ow.ly/FKe750Nhm8S

Tines No-code Automation For Security Teams

Risky Business publishes sponsored product demos to YouTube. They're a great way for you to save the time and hassle of trying to actually get useful information out of security vendors. You can subscribe to our product demo page on YouTube here.

In this video demo, Tines CEO and co-founder, Eoin Hinchy, demonstrates the Tines automation platform to host Patrick Gray.

Shorts

Ukraine: The Quiet Attacks Are the Most Dangerous

Ukraine's State Service of Special Communications and Information Protection (SSCIP) has published a report on Russian cyber tactics and how they evolved and changed over the last year. There are some interesting nuggets here.

The report describes shifting tactics over time. In the first half of the year attacks focussed on media and telecommunications, but this shifted towards energy infrastructure later in the year. Initial attacks were more disruptive, but the second half of the year saw increased focus on espionage and data theft.

The SSCIP also thinks that although Russian cyber operations designed to achieve some sort of psychological effect "attract the most attention from the mass media and society… slow and 'quiet' attacks aimed at espionage are actually much more dangerous".

Sorting the Trojans From the Tools

Techcrunch covers the steps the FBI took to prove that the NetWire RAT was malware rather than legitimate remote access software. The website that sold NetWire claimed it was a legitimate business tool, but the FBI paid for a version and could run the software's potentially intrusive features without any user indications or warnings. According to the FBI's affidavit, the agency accessed files, recovered passwords, took screenshots and ran a keylogger with "no visible windows or other indications on the infected computer's screen that would alert the user (victim) to the presence of the NetWire RAT".

There were lots of other "tells", including that NetWire was advertised on hacker forums and had been identified as malware by several security companies, but it is nice that the FBI did the work to put the question beyond any reasonable doubt.

Manipulating Standards? Isn't that NSA's Job??

The Carnegie Endowment has an excellent new report on how China manipulates international technical standards setting processes. This author has often heard that China is attempting to subvert international standards bodies, and this paper provides a very readable and nuanced exploration of what is really happening. It says that there are documented cases of manipulation where all Chinese participants were told to vote for a particular proposal, but despite that the report says "this type of manipulation appears to be rare and largely unsuccessful". Even so, there are still compelling reasons for concern and action. It argues that although the Chinese government is not a trustworthy actor when it comes to standards setting, the best response is to make it easier for US experts to participate in standards organisations.

Are You Interested in this Totally Legitimate Job Offer? Click Here!

Two reports this week indicate that both Iranian and North Korean APT groups are pushing the envelope when it comes to constructing personas to interact with targets. Mandiant described LinkedIn profiles created by a North Korean espionage group as "well designed and professionally curated". A report from Secureworks says an Iranian group masqueraded as an Atlantic Council employee.

At last! A Cyber Incident Reporting Framework for the Wonks

The Cyber Threat Alliance and the Institute for Security and Technology have released a global edition of its cyber incident reporting framework. The document is aimed at national cyber security authorities and lawmakers and it explains why you might want organisations to report cyber incidents and what information you should ask for. It's a dry subject, but the document is good and will be positively useful for cyber authorities looking to spin up reporting requirements

Risky Biz Talks

In addition to a podcast version of this newsletter (last edition here), the Risky Biz News feed (RSS, iTunesor Spotify) also publishes interviews.

In our last "Between Two Nerds" discussion Tom Uren and The Grugq discuss talent identification pipelines that different cyber powers use.

From Risky Biz News:

ODNI report highlights China as the US' biggest cyber threat: The Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) has published this week its yearly threat assessment, a report that aggregates intelligence insights on the US's main adversaries.

The 40-page unclassified report [PDF] covers a wide variety of topics ranging from military capabilities to space programs and economic threats. Cyber and influence operations were also included, which we will try to summarize here—in case you don't want to read the whole thing or watch the hearing. [more at Risky Business News]

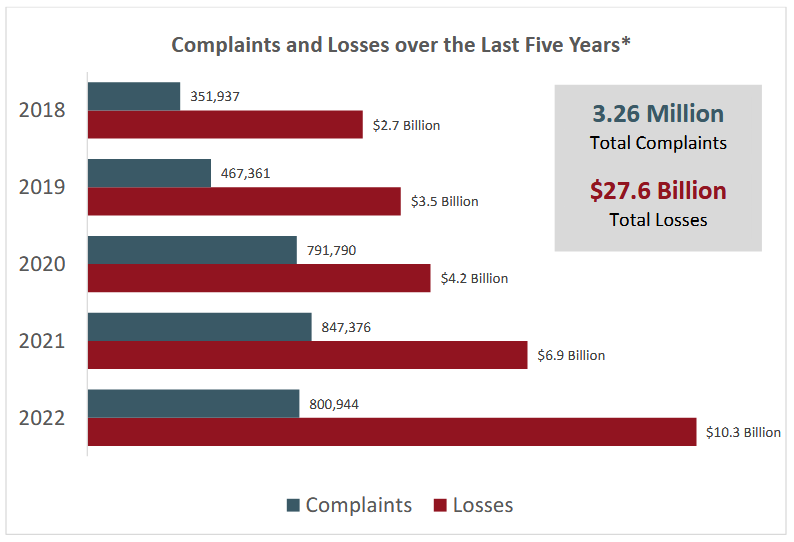

BEC loses top spot in FBI Internet Crime report: The Federal Bureau of Investigation has released its yearly internet crime report [PDF], and after seven years of dominance, business email compromise has lost the top spot to a "rising star"—namely, investment fraud.

Since its first edition, the IC3 report, as it's most commonly known, has been reporting losses at an increasing rate each year, and 2022 continued that trend. The FBI says that last year, users reported losing more than $10.3 billion to various forms of cybercrime, a 50% increase from 2021's $6.9 billion figure.

But things get interesting when we break down the numbers per category. While BEC ($2.7 billion) lost the top spot to investment fraud ($3.3 billion), both crime types combined accounted for more than half of the losses reported last year. [more at Risky Business News]